Did you see the jaw-dropping 60 Minutes segment last month about the young jazz pianist and prodigy, Matthew Whitaker? He can play any piece of music after hearing it just once.

Whitaker is black. He’s blind. And he’s brilliant. See for yourself.

Stories like this are a welcome antidote to the tsunami of divisive, soul-crushing politics that slams us in the face every day.

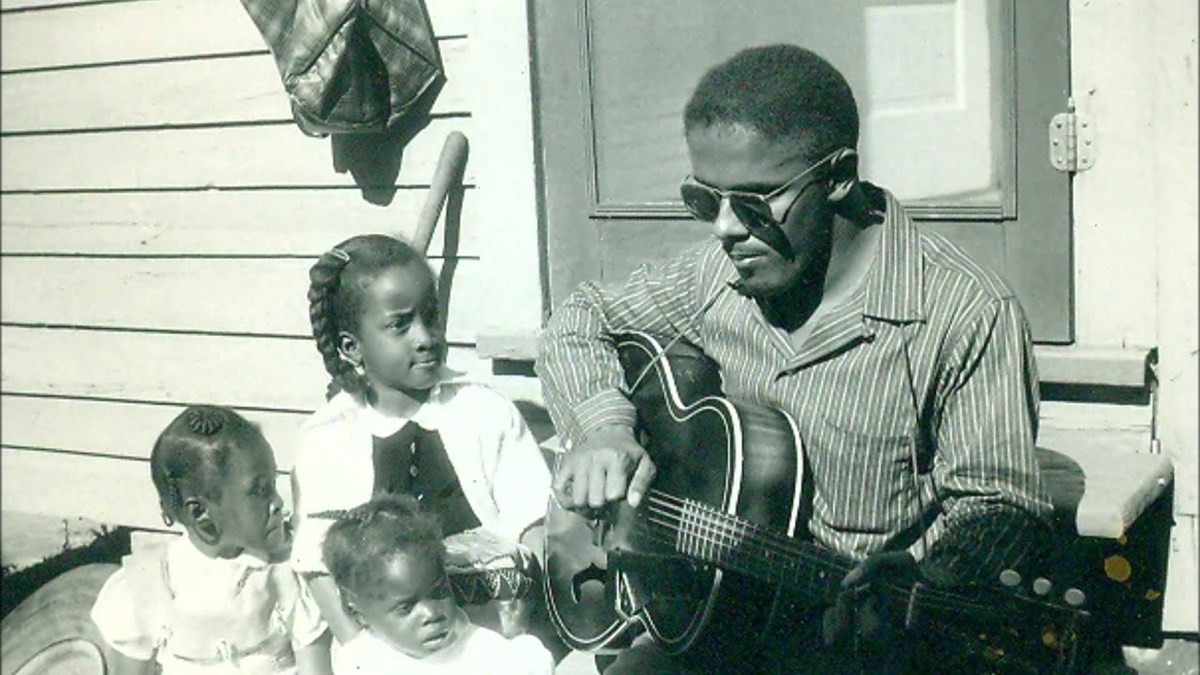

This extraordinary young man is one of a remarkable number of musicians in American history who share the three B’s—black, blind and brilliant. They include names like Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, Arizona Dranes, Art Tatum, and Marcus Roberts. They persevered against both their handicap and prejudice against their skin color. Their brilliance helped them overcome and develop grateful audiences across all spectrums of race, politics, regions and age.

Spurred by the Whitaker story, I wanted to write about musicians like him. The problem was, so many black, blind and brilliant musicians grace our history that I had to come up with a rationale for choosing which ones to focus on. Then it hit me—why not zero in on those who were known for the adjective “Blind” in their names? Believe it or not, that still yields at least ten individuals.

Below are a few words about each of those ten, along with links to samples of the music they produced. It is all quintessential Americana—a mix of homespun blues, gospel, bluegrass, jazz and ragtime, as well as a sprinkling of other genres. Expressive and heartfelt, their music should renew our appreciation of the contributions these people made to music and culture.

1. Blind Lemon Jefferson (1893-1929)

Biographer Robert Uzzel writes that Jefferson was regarded as “the first downhome blues singer to enjoy commercial success” and “the first truly great male blues singer to record” his music. Two of his best-known songs were See that My Grave is Kept Clean and Black Snake Moan. He was a big reason that Paramount became the #1 recording company for the blues during the Roaring ‘20s.

2. Blind Willie Johnson (1897-1945)

“Johnson played in a bluesy style, but his music was sacred, based as much on African American gospel traditions as it was on the blues,” writes J. Poet in Lonestar Music magazine. “His bone-rattling baritone delivered messages of salvation and perdition that are still relevant today.” Listen to Johnson’s Nobody’s Fault But Mine and see if you agree.

3. Blind Boy Fuller (ca. 1904-1941)

His musical career was briefly interrupted by a prison term for shooting his wife in the leg, but Fuller’s popularity (except with his wife) never waned while he was alive. He was regarded as one of the best practitioners of the guitar style known as Piedmont Blues. Paul Oliver in Blues Off the Record writes, “His style of singing was rough and direct, and his lyrics were explicit and uninhibited, drawing on every aspect of his experience as an underprivileged, blind black man on the streets—pawnshops, jailhouses, sickness, death—with an honesty that lacked sentimentality.” Check out Fuller’s I’m a Rattlesnakin’ Daddy.

4. Blind Tom Wiggins (1849-1908)

Born a slave and blind at birth, the infant Wiggins and his parents were sold in 1850 to the first southern newspaper editor to advocate for secession. By all accounts, if he were alive today, he would be regarded as an autistic savant. His amazing abilities included memorizing entire conversations and musical compositions, repeating them flawlessly after one hearing. His owner, John Bethune, made a fortune from touring Wiggins around the U.S. Learn more about him below.

5. Blind John Davis (1913-1985)

The music of boogie-woogie pianist and blues singer Blind John Davis possessed an elegant sophistication that audiences in both America and Europe loved from the start. In 1952 he traveled to Europe in what biographer Bill Dahl claims “may well have been the first overseas jaunt for any American blues artist.” Thereafter, Europe is where Davis mostly performed until his death in 1985. I’m personally a latecomer to jazz, but it was recordings of Davis (as well as those of black artists Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington) that turned me on to it, including his songs, Lonesome Blues and No Mail Today.

6. Blind Joe Reynolds (ca. 1900-1968)

Reynolds lost his eyes in a shotgun blast to the face in the 1920s but that didn’t stop him from developing his own uncanny accuracy with a pistol. In Chasin’ that Devil Blues, Gayle Dean Wardley noted that “he could judge the position of a target by sound alone.” He could be shrill in both message and voice but his music attracted a loyal following. Cold Woman Blues is a good example.

7. Blind Willie McTell (1898-1955)

From Michael Gray’s book, Hand Me My Travelin’ Shoes: In Search of Willie McTell comes this colorful description: “Whether selling high-quality homemade bootleg whisky out of a suitcase, bragging about crowds of women chasing him, or suffering a stroke while eating barbecue under a tree, McTell emerges from this book a cheerful, outgoing, engaging individualist with seemingly limitless self-confidence.” This selection of his tunes reveals the magnetic resonance of McTell’s voice: Country Blues, Ragtime and Piedmont Blues.

8. Blind Boys of Alabama (1939-present)

This is a gospel music group founded in 1939 that featured many different black individuals over the years. It numbered five or six at a time and since the founding more than 80 years ago, almost all have been blind or partially so. In a 2011 Mother Jones interview, the group’s Ricky McKinnie said, “Our disability doesn’t have to be a handicap. It’s not about what you can’t do. It’s about what you do. And what we do is sing good gospel music.” Here’s a glimpse of what the group’s 1964 team could do: Too Close to Heaven.

9. Blind Snooks Eaglin (ca. 1936-2009)

Known as the “Little Ray Charles” and “The Human Jukebox,” Blind Snooks Eaglin dropped out of a school for the blind at the age of 14 to pursue his eclectic musical interests: rock and roll, blues, Latin, country and jazz. Neither his bandmates nor his audiences knew what he would play next from his repertoire of some 2,500 songs. One More Drink is one of them.

10. Blind Arthur Blake (1896-1934)

The ragtime blues guitar legend Blind Arthur Blake will bring a smile to your face with his West Coast Blues. Jas Obrecht cites a 1927 promotional booklet from Blake’s employer, Paramount:

We have all heard expressions of people ‘singing in the rain’ or ‘laughing in the face of adversity,’ but we never saw such a good example of it, until we came upon the history of Blind Blake. Born in Jacksonville, in sunny Florida, he seemed to absorb some of the sunny atmosphere—disregarding the fact that nature had cruelly denied him a vision of outer things. He could not see the things that others saw—but he had a better gift. A gift of an inner vision, that allowed him to see things more beautiful. The pictures that he alone could see made him long to express them in some way—so he turned to music. He studied long and earnestly—listening to talented pianists and guitar players—and began to gradually draw out harmonious tunes to fit every mood.

I think Obrecht is right in suggesting that Blind Arthur Blake “lived the lines he sang” in Poker Woman Blues:

Sometime I’m rich, sometime I ain’t got a cent, But I’ve had a good time everywhere I went.

These black, blind and brilliant musicians evoked a wide range of emotions in the audiences who loved their music. They were a unifying force because what they did tended to bring all peoples together. They touched every chord of life in ways unequaled in any other part of the world. Wherever you are on the planet, when you think of blues, gospel, bluegrass, jazz, or ragtime, you think of America because of people such as these talented ten.

I don’t need a Black History Month to celebrate the black, blind and brilliant who left such an indelible mark on American culture. I celebrate them every day of the year.