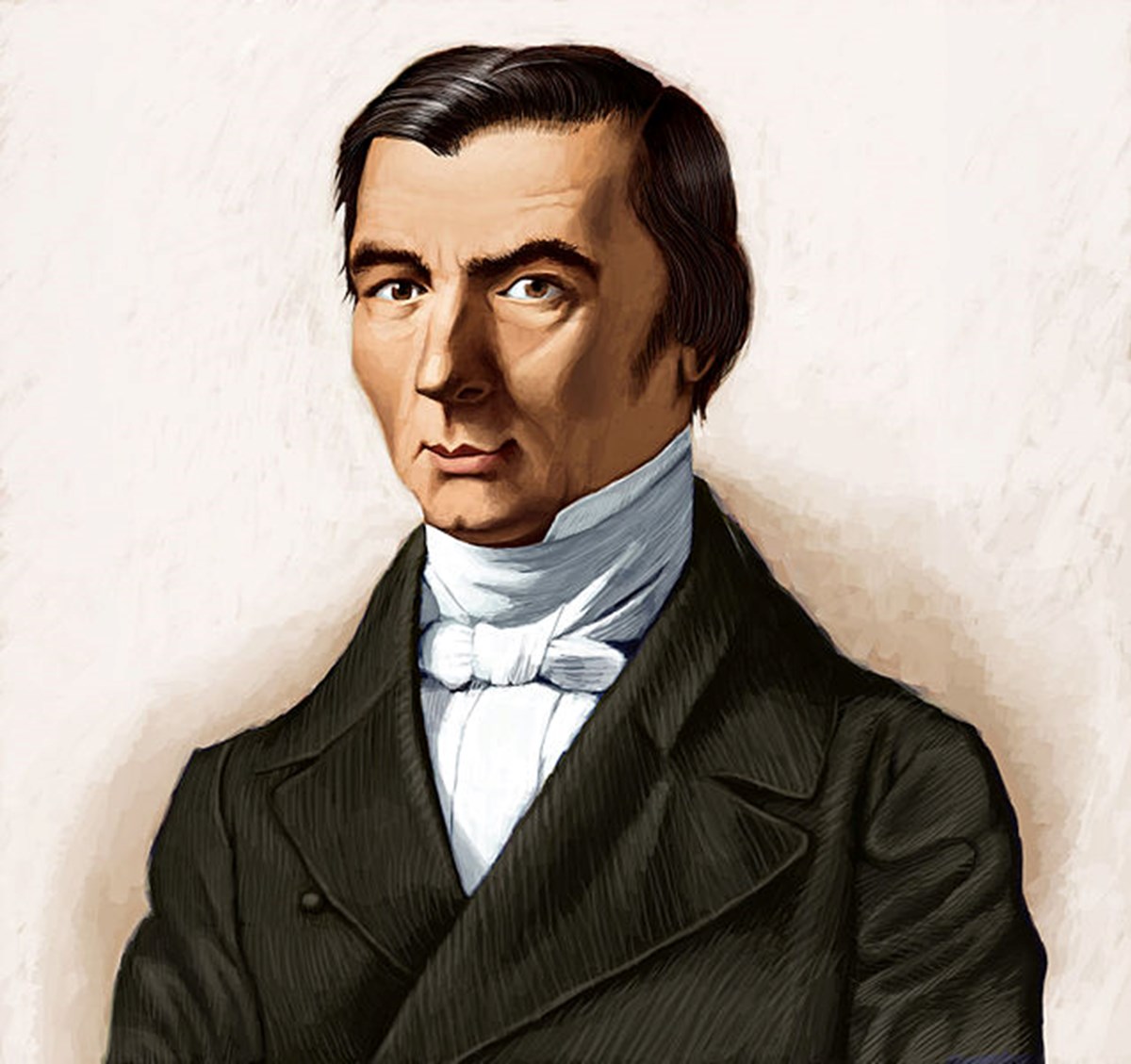

June 30 is Frédéric Bastiat’s birthday. For those who love liberty, it is a day to celebrate his masterpieces, including The Law and his essay, “Government,” not to mention some of the best reductio ad absurdum arguments ever (such as the Candlemakers’ Petition and the Negative Railway). But even his fans sometimes forget that he ran for, and held, political office. That is unfortunate, given that what a principled libertarian politician stood for is very instructive.

That is why it is worth using Bastiat’s birthday to consider his election manifesto of 1846, his first try for office (which he lost). The entire manifesto is available online, but for a taste, consider the truncated version below:

To the Electors of the District of Saint-Sever, July 1846

[I suggest] a rallying principle…one simple, true, clear, fertile, practical idea…a party exclusively representing, in all its scope and entirely, the interests of the governed, of the taxpayers.

There are things that can be done only by the collective force or established authority, and others that should be left to private activity.

The fundamental problem in political science is to know what pertains to each of these two modes of action.

Public administration and private activity both have our good in view. But their services differ in that we suffer the former under compulsion and accept the latter of our own free will, whence it follows that it is reasonable to entrust the former only with what the latter is absolutely unable to carry out.

I believe that, when the powers that be have guaranteed to each and every one the free use and the product of his or her faculties, repressed any possible misuse, maintained order, secured national independence, and carried out certain tasks in the public interest which are beyond the power of the individual, then they have fulfilled just about all their duty.

Beyond this sphere…everything belongs to the field of private activity, under the eye of public authority, whose role should be one only of vigilance and of repression of disorder.

If that great and fundamental boundary were thus established, then…On the one condition that he or she did not encroach on the freedom of others, each citizen would fully and completely enjoy the free exercise of his or her physical, mental, and moral faculties.

Freed from all regulating constraint, society would then be in the best possible position to develop its riches, its education, and its morality.

But even if there were agreement on the limits of public authority, it is no easy matter to force it and maintain it within those limits.

Government power…naturally tends to grow. It feels cramped within its supervisory mission. Now, its growth is hardly possible without a succession of encroachments upon the field of individual rights. The expansion of government power means usurping some form of private activity, transgressing the boundary…between what is and what is not its essential function.

Government becomes all the more costly as it becomes oppressive…each of its intrusions implies creating some new administration, instituting some fresh tax, so that our freedom and our purse inevitably share a common destiny.

Consequently, if the public understands and wishes to defend its true interests, it will halt authority as soon as the latter tries to go beyond its sphere of activity…to deny authority the resources with which it could carry out its encroachments.

[This does] not consist in hindering the government in its essential activity…It consists solely in keeping the government within its limits; in preserving the sphere of freedom and of private activity as completely and extensively as possible.

[Beyond that] we would have to pay, not to be served but to be serfs, not to preserve our freedom but to lose it

In [citizens’] interest, let there be good public management of what can unfortunately not be carried out otherwise. In their interest also, let there be complete and utter freedom in everything else.

It is entirely up to the public to decide how, to what extent, and at what cost it means to have things managed, otherwise representative government would be nothing but a meaningless deception and the sovereignty of the people a meaningless expression. Now, having recognized the tendency of any government to grow indefinitely…on the subject of its own limits, if you leave it to the government itself…then you might as well put your wealth and your freedom at its disposal. To expect a government to draw from within itself the strength to resist its natural expansion is to expect from a falling stone the energy to halt its fall.

The organized vigilance of the public…[should] help [government] within the sphere of their legitimate duties, but…mercilessly confine them within that sphere…This natural form of opposition…attacks the government neither in those who hold office…it gets to the bottom of things and pursues evil to its very roots.

If one day a member [said] “Gentlemen, fight among yourselves over power, all I seek to do is restrain it; wrangle over how to manipulate the budget, all I wish to do is to reduce it”…[opposing parties], apparently so bitterly opposed, will very soon pull together to stifle the voice of that faithful representative. They will call him a utopian, a theoretician, a dangerous reformer…they will heap scorn upon him; they will turn the venal press against him.

Anyone who has created a product should have the option of exchanging it, as well as of using it himself. Exchange is therefore an integral part of the right to property. Now we have not instituted and we do not pay government in order to deprive us of that right, but on the contrary in order to guarantee us that right in its entirety. None of the government’s encroachments has had more disastrous consequences than its encroachment on the exercise of our faculties and on our freedom to dispose of their products…based on the most flagrant plunder.

When the state becomes the distributor and regulator of profits, all sectors of industry tug at it this way and that to tear from it a shred of monopoly…by restraining the government you consolidate it rather than endanger it.

It is the inordinate expansion of its power that makes the state have recourse to the most hateful tax invention. When a nation…is forever begging for state intervention, then it must resign itself to being mercilessly ransomed; for the state can do nothing without finance…Does [it] call on its government to intervene in every matter? In that case, it should no longer complain about being overburdened.

I…expect the welfare of my country to result from…our good faith in supporting the government in the useful exercise of its essential powers and from our firm determination to restrict it to those limits. The government has to be firm facing enemies from within and from without, for its mission is to keep the peace at home and abroad. But it must leave to private activity everything that is within the latter’s competence. Order and freedom depend on those conditions.

As a politician as well as a writer, Frédéric Bastiat advocated a government that would, by focusing narrowly on ensuring that individuals “did not encroach on the freedom of others,” guarantee each citizen the ability to “fully and completely enjoy the free exercise of his or her physical, mental, and moral faculties.” And he did so surrounded by a sea of special interests whose plans for piracy he threatened. That took principles and courage. We should remember both on his birthday.