Download:

Introduction

For most of human history, until quite recently, education and schooling were separate and distinct. When the Pilgrims arrived on the shores of the New World in 1620, searching for personal liberty and freedom of expression, the expectation for educating children was firmly rooted in the family. It remained there for over two hundred years, even as an informal network of public and private schools sprouted to offer education in classrooms for those parents who chose it. Parents remained squarely responsible for the education of their children, whether at home, in schools, through apprenticeships, or all three.

It wasn’t until the mid-nineteenth century that this all changed. With the onset of compulsory schooling statutes that mandated attendance in schools, education gradually became synonymous with schooling. Parents, particularly immigrant parents who threatened the dominant Anglo-Saxon Protestant cultural norms of the time, lost power and autonomy. Their children were increasingly educated in “common school” classrooms, and attempts to create an alternative schooling system, such as Catholic parochial schools, were hotly criticized and contested. Homeschooling became an option mostly for the elites, like Horace Mann, the influential common school reformer who is credited with passing the nation’s first compulsory schooling law in Massachusetts in 1852. Mann’s wife homeschooled their three children.

Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, and for much of the 20th century, children and adolescents spent increasingly longer portions of their days and years in mass schooling. Homeschooling fell out of favor, even among the elites, and public schools vastly eclipsed private schools in terms of enrollment. The high school was invented, and kindergartens were incorporated into primary schools. The rise of mass schooling led to a growing separation of children from their families and their broader communities. Most of their childhood and adolescence were spent in school.

In the 1960s and ’70s, parents began to take back control of their children’s education. Liberals and conservatives alike removed their children from public schools to homeschool them, and led an effort to make homeschooling legally recognized in all 50 states by 1993. At the same time, some parents and educators embraced the idea of “unschooling,” or Self-Directed Education, that further sought to separate education from schooling—including school-at-home. These unschoolers blurred the lines between formal notions of learning and a more authentic, personalized approach to education focused on individual autonomy and real-life immersion in the broader community. As we nestle into the 21st century, with its vast technological infrastructure and unprecedented pace of innovation, the principles of unschooling have never been more relevant or essential—both for individuals and for society.

This collection of FEE.org articles digs deeper into the fascinating evolution of education in America, from its family-centered origins to the rise of compulsory schooling, and the gradual separation of education from schooling over the last 50 years. The anthology is divided into three sections. The first part describes the history and impact of compulsory schooling on education in the U.S., including modern efforts to break its stranglehold with education choice mechanisms and free market principles. The second section explores the rise of the contemporary homeschooling movement, including the ongoing challenges homeschooling parents face from government overreach. The final section elaborates on the ideals and practices of unschooling and Self-Directed Education, which place learners in charge of their own education, following their own distinct passions, while supported and nurtured by their families and communities.

Many of these articles are presented in the first-person as I share my perspectives as an unschooling mom to four never-been-schooled children, while others reflect broader research and trends exposed through my ongoing work as an education policy writer. I hope you will find this blend of policy and practice, of ideas and implementation valuable as you trace the past, present, and future of compulsory schooling, homeschooling, and unschooling.

Compulsory Schooling

Compulsory Schooling Is Incompatible with Freedom

If we care about freedom, we should reject compulsory schooling. A relic of 19th-century industrial America, compulsory schooling statutes reduced the broad and noble goal of an educated citizenry into a one-size-fits-all system of state-controlled mass schooling that persists today.

Horace Mann, the designer of the nation’s first compulsory schooling law in Massachusetts in 1852, saw taxpayer-funded, universal compulsory schooling as a way to mold children into moral, democratic citizens. He famously said: “Men are cast-iron, but children are wax.”

Despite the fact that he homeschooled his own children, Mann built the Prussian-inspired foundation for the modern government schooling apparatus, cementing education’s enduring association with schooling. His biographer, Jonathan Messerli, writes of Mann: “That in enlarging the European concept of schooling, he might narrow the real parameters of education by enclosing it within the four walls of the public school classroom.”[1]

Founding Father of Forced Education

For Mann and his colleagues, compulsory schooling represented a dramatic leap from the Founding Fathers who influenced their vision. Thomas Jefferson, for example, recognized the essential connection between education and freedom, writing in 1816: “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.”[2]

Jefferson supported a decentralized framework of education, free to the poor; but, unlike Mann, he recognized that making such a system compulsory and government-controlled would be a threat to liberty. Jefferson wrote in 1817: “It is better to tolerate the rare instance of a parent refusing to let his child be educated, than to shock the common feelings and ideas by the forcible asportation and education of the infant against the will of the father.”[3]

Despite Jefferson’s warnings, compulsory schooling laws were enacted and expanded during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, mandating school attendance under a legal threat of force. Some 20th century education philosophers and social reformers, like John Dewey, aimed to lessen the impact of forced schooling, striving to make classrooms and curricula more relevant to children’s experiences and more hands-on and experimental.

What these well-meaning reformers often ignored, however, was the inherent conflict between freedom and compulsion in mass schooling. One cannot be truly free within a mandatory, coercive system of social control.

In 1964, just over a century after the initial onset of state-controlled compulsory schooling, Paul Goodman wrote his scathing treatise, Compulsory Mis-education, describing the key failures of compulsory schooling. He wrote that “education must be voluntary rather than compulsory, for no growth to freedom occurs except by intrinsic motivation. Therefore the educational opportunities must be various and variously administered. We must diminish rather than expand the present monolithic school system.”[4]

Even as social reformers ranging from A.S. Neill (Summerhill, 1960) to John Holt (How Children Fail, 1964; How Children Learn, 1967) to Ivan Illich (Deschooling Society, 1970) wrote about the serious problems with forced schooling, compulsory education laws tightened and expanded worldwide in the latter half of the 20th century.

The United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child (adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1989 and ratified later by all UN member nations except for the United States) asserts: “The child is entitled to receive education, which shall be free and compulsory.” According to the U.N. every child has a right to a forced education, mandated by law and compelled by the state.[5]

Empowering Parents

Today, as compulsory schooling consumes more of a child’s life than ever before, beginning in toddlerhood and extending into late-adolescence for much of each day and year, many parents and educators are recognizing the disconnect between forced schooling and freedom. Increasingly, they are choosing—or creating—alternatives to school.

A rising number of “free schools” and Sudbury-type democratic schools, like those promoted by A.S. Neill, are opening nationwide, enabling young people to direct their own education free from coercion. Homeschooling is booming, and the philosophy of unschooling, or self-directed education, advocated by John Holt and others is growing in popularity and influence. Lawmakers in some states are urging a repeal of antiquated compulsory schooling laws, and are re-empowering parents with more education choice measures.

These are promising signals of a quiet exodus from mass schooling, as more people realize that freedom and compulsion make strange bedfellows.

[1] Messerli, Jonathan. 1972. Horace Mann: A Biography. New York: Knopf.

[2] Jefferson, Thomas. Extract from a letter from Thomas Jefferson to Charles Yancey in Quotes by and about Thomas Jefferson. Jan. 6, 1816.

[3] Jefferson, Thomas.1904. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. Vol. 17. Issued under the auspices of the Jefferson Memorial. Washington, D.C. p. 423.

[4] Goodman, Paul. 1966. Community Mis-Education and the Community of Scholars. New York: Random House.

[5] United Nations Human Rights. (1959). Declaration of the Rights of the Child. “Principle 7” [online] Available at: https://www.unicef.org/malaysia/1959-Declaration-of-the-Rights-of-the-Child.pdf

Milton Friedman Was Right to Call Them “Government Schools”

Milton Friedman was the 1976 Nobel-prize winning economist who promoted free-market ideals and limited government. The Economist called him “the most influential economist of the second half of the 20th century. . . possibly of all of it.”[1]

He died in 2006, but one of his lasting legacies is EdChoice, formerly the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, the organization Friedman and his economist wife, Rose Director Friedman, founded in 1996. The non-profit strives to “advance educational freedom and choice for all as a pathway to successful lives and a stronger society.”

It was fitting that on his birthday in 2017, Mr. Friedman was mentioned in The New York Times; but it wasn’t to offer birthday wishes. Instead, an opinion article written by journalist Katherine Stewart, author of The Good News Club: The Christian Right’s Stealth Assault on America’s Children, criticizes Friedman and his current education choice followers.

Friedman’s Take

Stewart alludes to Friedman’s influential 1955 paper advocating education choice and school vouchers for parents. In that paper, Friedman offers the foundation for modern school choice theory. He begins with a statement as true today as it was then:

The current pause, perhaps reversal, in the trend toward collectivism offers an opportunity to reexamine the existing activities of government and to make a fresh assessment of the activities that are and those that are not justified.[2]

Friedman goes on to advocate for the “denationalization of education” through choice and vouchers. He writes:

Given, as at present, that parents can send their children to government schools without special payment, very few can or will send them to other schools unless they too are subsidized. Parochial schools are at a disadvantage in not getting any of the public funds devoted to education; but they have the compensating advantage of being run by institutions that are willing to subsidize them and can raise funds to do so, whereas there are few other sources of subsidies for schools. Let the subsidy be made available to parents regardless where they send their children—provided only that it be to schools that satisfy specified minimum standards—and a wide variety of schools will spring up to meet the demand. Parents could express their views about schools directly, by withdrawing their children from one school and sending them to another, to a much greater extent than is now possible.[3]

“Government Schools”

In her op-ed, entitled “What ‘Government School’ Means,” Stewart writes at length about the term “government schools,” a phrase Friedman used and that many of us use today to describe compulsory, taxpayer-funded, government-controlled schooling. She argues that referring to public schools as “government schools” is rooted in a racist past of “American slavery, Jim Crow-era segregation, anti-Catholic sentiment and a particular form of Christian fundamentalism,” and she attacks the marriage of those advocating economic and religious freedom. Stewart writes:

Many of Friedman’s successors in the libertarian tradition have forgotten or distanced themselves from the midcentury moment when they formed common cause with the Christian right.[4]

In its modern usage, as well as Friedman’s use of the term, the phrase “government schooling” is often used to draw attention to increasing federal and state control of education, and the corresponding weakening of parental influence and choice. For instance, in his 1991 Wall Street Journal op-ed, former New York State Teacher of the Year, John Taylor Gatto, writes:

Government schooling is the most radical adventure in history. It kills the family by monopolizing the best times of childhood and by teaching disrespect for home and parents.[5]

In her article, Stewart links compulsory government schooling with democracy; She concludes:

When these people talk about “government schools,” they want you to think of an alien force, and not an expression of democratic purpose. And when they say “freedom,” they mean freedom from democracy itself.[6]

But for Friedman and his current school choice followers, freedom from a government-controlled, compulsory institution is a fully democratic expression that widens opportunity and expands liberty. School choice beyond government schools also frees many young people from what can be an oppressive childhood mandate.

Facilitating Freedom with School Choice

As a teacher for 30 years, Gatto saw first-hand the harm that compulsory government schooling can cause. In his Wall Street Journal article he writes:

“Good schools don’t need more money or a longer year; they need real free-market choices, variety that speaks to every need and runs risks. We don’t need a national curriculum or national testing either. Both initiatives arise from ignorance of how people learn or deliberate indifference to it. I can’t teach this way any longer. If you hear of a job where I don’t have to hurt kids to make a living, let me know.”[7]

School choice measures can promote freedom and opportunity, and reduce harm to children. They can also help to limit the role of government while augmenting the role of parents and educators.[8]

Friedman concludes his 1955 paper describing how school choice measures can facilitate freedom. He states that these measures would lead to “a sizable reduction in the direct activities of government, yet a great widening in the educational opportunities open to our children. They would bring a healthy increase in the variety of educational institutions available and in competition among them. Private initiative and enterprise would quicken the pace of progress in this area as it has in so many others. Government would serve its proper function of improving the operation of the invisible hand without substituting the dead hand of bureaucracy.”

[1] No Author. 2006. “Milton Friedman: An Enduring Legacy.” The Economist. https://www.economist.com/news/2006/11/17/an-enduring-legacy

[2] Friedman, Milton. 1955. “The Role of Government in Education.” Economics and the Public Interest, ed. Robert A. Solo. Reprinted online with permission from Rutgers University Press. http://la.utexas.edu/users/hcleaver/330T/350kPEEFriedmanRoleOfGovttable.pdf

[3] Ibid.

[4] Stewart, Katherine. 2017. “What the ‘Government Schools’ Critics Really Mean.” New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/31/opinion/donald-trump-school-choice-criticism.html

[5] Gatto, John Taylor. 1991. “I quit, I think.” Education Revolution. Reprinted 2011. http://www.educationrevolution.org/blog/i-quit-i-think/

[6] Stewart, 2017.

[7] Gatto, 1991.

[8] For more information on vouchers, see my 2018 article, “School Vouchers Give Parents More Choice in Education.” Foundation for Economic Education. https://fee.org/articles/school-vouchers-give-parents-more-choice-in-education/

The Devastating Rise of Mass Schooling

For generations, children learned in their homes, from their parents, and throughout their communities. Children were vital contributors to a homestead, becoming involved in household chores and rhythms from very early ages. They learned important, practical skills by observing and imitating their parents and neighbors—and by engaging in hands-on apprenticeships as teens—and they learned literacy and numeracy around the fireside.

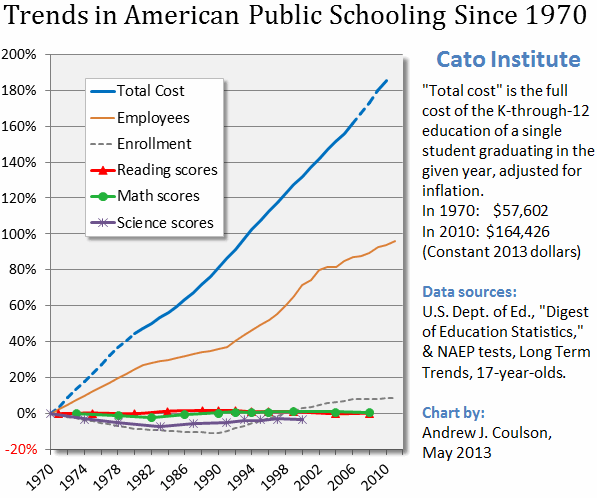

In fact, the literacy rate in Massachusetts in 1850 (just two years prior to the passage of the country’s first compulsory school attendance law there) was 97 percent.[1] According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the Massachusetts adult literacy rate in 2003 was only 90%.

In advocating for compulsory schooling statutes, Horace Mann and his 19th century education reform colleagues were deeply fearful of parental authority—particularly as the population became more diverse and, in Massachusetts as elsewhere, Irish Catholic immigrants challenged existing cultural and religious norms. “Those now pouring in upon us, in masses of thousands upon thousands, are wholly of another kind in morals and intellect,” mourned the Massachusetts state legislature regarding the new Boston Irish immigrants.[2]

In his book, Horace Mann’s Troubling Legacy, University of Vermont professor, Bob Pepperman Taylor, elaborates further on the 19th-century distrust of parents, particularly immigrant parents, and its role in catalyzing compulsory schooling. Pepperman Taylor explains that “the group receiving the greatest scolding from Mann is parents themselves. He questions the competence of a great many parents, but even worse is what he takes to be the perverse moral education provided to children by their corrupt parents.”[3] Forced schooling was then intended as an antidote to those “corrupt parents,” but not, presumably, for morally superior parents like Mann, who continued to homeschool his own three children with no intention of sending them to the common schools he mandated for others. As Mann’s biographer, Jonathan Messerli writes:

From a hundred platforms, Mann had lectured that the need for better schools was predicated upon the assumption that parents could no longer be entrusted to perform their traditional roles in moral training and that a more systematic approach within the public school was necessary. Now as a father, he fell back on the educational responsibilities of the family, hoping to make the fireside achieve for his own son what he wanted the schools to accomplish for others.[4]

As mass schooling has expanded over the past 165 years, parental empowerment has declined precipitously. Institutions have steadily replaced parents, with alarming consequences. Children are swept into the mass schooling system at ever-earlier ages, most recently with the expansion of government-funded preschool and early intervention programs. Most young people spend the majority of their days away from their families and in increasingly restrictive, test-driven schooling environments. It is becoming more widely acknowledged that these institutional environments are damaging many children. Boston College psychology professor, Dr. Peter Gray, writes:

School is a place where children are compelled to be and where their freedom is greatly restricted—far more restricted than most adults would tolerate in their workplaces. In recent decades, we have been compelling our children to spend ever more time in this kind of setting, and there is strong evidence (summarized in my recent book [Free To Learn]) that this is causing serious psychological damage to many of them.[5]

For teenagers, the impact of mass schooling can be even more severe. Largely cut off from the authentic adult world in which they are designed to interact, many adolescents rebel with maladaptive behaviors ranging from anger and angst to substance abuse and suicide. As Dr. Robert Epstein writes in his book, The Case Against Adolescence: Rediscovering the Adult in Every Teen:

Driven by evolutionary imperatives established thousands of years ago, the main need a teenager has is to become productive and independent. After puberty, if we pretend our teens are still children, we will be unable to meet their most fundamental needs, and we will cause some teens great distress.[6]

It is time to hand the reins of education back to parents and once again prioritize authentic learning over mass schooling. Parents know best. They should be able to choose freely from a wide variety of innovative, agile education options, rather than rely on a one-size-fits-all mass schooling model. By positioning parents to take back control of their children’s education—to reclaim their rightful place as experts on their own children—we can foster more education options and better outcomes for children and society.

[1] Total Massachusetts population in 1850 was 994,514; total illiteracy rate in Massachusetts in 1850 was 28,345.

[2] Peterson, Paul E. 2010. Saving Schools: From Horace Mann to Virtual Learning. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, p. 26.

[3] Pepperman Taylor, Bob. 2010. Horace Mann’s Troubling Legacy: The Education of Democratic Citizens. Kansas: University Press of Kansas.

[4] Messerli, Jonathan. 1972. Horace Mann: A Biography. New York: Knopf.

[5] Gray, Peter. 2013. “School Is a Prison—And Damaging our Kids.” Salon. https://www.salon.com/2013/08/26/school_is_a_prison_and_damaging_our_kids/

[6] Epstein, Robert. 2007. The Case Against Adolescence: Rediscovering the Adult in Every Teen. California: Quill Driver Books/Word Dancer Press, Inc.

How Schooling Crushes Creativity

In 2006, educator and author Ken Robinson gave a TED Talk called, “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” At over 50 million views, it remains the most viewed talk in TED’s history.

Robinson’s premise is simple: our current education system strips young people of their natural creativity and curiosity by shaping them into a one-dimensional academic mold. This mold may work for some of us, particularly, as he states, if we want to become university professors; but for many of us, our innate abilities and sprouting passions are at best ignored and at worst destroyed by modern schooling.

In his TED Talk, Robinson concludes:

I believe our only hope for the future is to adopt a new conception of human ecology, one in which we start to reconstitute our conception of the richness of human capacity. Our education system has mined our minds in the way that we strip-mine the earth: for a particular commodity. And for the future, it won’t serve us. We have to rethink the fundamental principles on which we’re educating our children.[1]

Education by Force

Robinson echoes the concerns of many educators who believe that our current forced schooling model erodes children’s vibrant creativity and forces them to suppress their self-educative instincts. In his book, Free To Learn, Boston College psychology professor, Dr. Peter Gray, writes:

In the name of education, we have increasingly deprived children of the time and freedom they need to educate themselves through their own means. . . We have created a world in which children must suppress their natural instincts to take charge of their own education and, instead, mindlessly follow paths to nowhere laid out for them by adults. We have created a world that is literally driving many young people crazy and leaving many others unable to develop the confidence and skills required for adult responsibility.[2]

Compelling research shows that when children are allowed to learn naturally, without top-down instruction and coercion, the learning is deeper and much more creative than when children are passively taught. University of California at Berkeley professor Alison Gopnik finds in her studies with four-year-olds, as well as similar studies out of MIT, that self-directed learning—not forced instruction—elevates both learning outcomes and creativity.

Gopnik’s research involved young children learning how to manipulate a specific toy that would make certain sounds or exhibit certain features in certain sequences. She found that when children were directly taught how to use the toy they were able to replicate the results and quickly get to the “right answer” on their own by loosely mimicking what the teacher demonstrated.

But when the children were instead allowed to learn without direct instruction—to play with the toy, explore its features, and discover its capabilities on their own—they were able to get to the “right answer” in fewer steps than the taught children. The self-directed children also revealed other parts of the toy that could do interesting things—which the taught children did not discover.

Gopnik summarizes this research in her Slate article, stating:

Perhaps direct instruction can help children learn specific facts and skills, but what about curiosity and creativity—abilities that are even more important for learning in the long run? . . . While learning from a teacher may help children get to a specific answer more quickly, it also makes them less likely to discover new information about a problem and to create a new and unexpected solution.[3]

Learning Not Schooling

Conformity may have been the social and economic goal of the 19th-century architects of the top-down, compulsory schooling model, but the 21st-century economy demands creativity. We now need a learning model of education, rather than a schooling one.

As former Google CEO Eric Schmidt stated, “every two days we create as much information as we did from the dawn of civilization up until 2003.”[4] It is impossible to think that an archaic, industrial model of forced schooling can keep pace with a new, technologically-enabled, information-saturated economy that requires agility, inventiveness, collaboration, and continuous knowledge-sharing. A truly transformative 21st-century education model will cultivate, rather than crush, human creativity.

[1] Robinson, Ken. 2006. “Do Schools Kill Creativity?” Filmed February 2006 at TED2006, 19:222. https://www.ted.com/talks/ken_robinson_says_schools_kill_creativity.

[2] Gray, Peter. 2013. Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant, and Better Students for Life. New York: Basic Books.

[3] Gopnik, Alison. 2011. “Why Preschool Shouldn’t Be Like School.” Slate. http://www.slate.com/articles/double_x/doublex/2011/03/why_preschool_shouldnt_be_like_school.html

[4] Siegler, M.G. 2010. “Eric Schmidt: Every 2 Days We Create As Much Information As We Did Up To 2003.” Tech Crunch. https://techcrunch.com/2010/08/04/schmidt-data/

Factory-Like Schools Are the Child Labor Crisis of Today

Most American children and teenagers wake early, maybe gulp down a quick breakfast, and get transported quickly to the building where they will then spend the majority of their day being told what to do, what to think, how to act. An increasing number of these young people will spend their entire day in this building, making a seamless transition from the school day to afterschool programming, emerging into the darkness of dinnertime. For others, there are structured after-school activities, followed by hours of tedious homework. Maybe, if they’re lucky, they’ll get to play a video game before bed—a rare moment when they are in control.

There is mounting evidence that increasingly restrictive schooling, quickly consuming the majority of childhood, is damaging children. Rates of childhood anxiety, depression, behavioral problems, and other mental illness are surging. Teenage suicide rates have doubled for girls since 2007, and have increased 30 percent for teenage boys. Eleven percent of children are now diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and three-quarters of them are placed on potent psychotropic medications for what Boston College psychology professor Dr. Peter Gray describes as a “failure to adapt to the conditions of standard schooling.” Dr. Gray goes on to explain:

It is not natural for children (or anyone else, for that matter) to spend so much time sitting, so much time ignoring their own real questions and interests, so much time doing precisely what they are told to do. We humans are highly adaptable, but we are not infinitely adaptable. It is possible to push an environment so far out of the bounds of normality that many of our members just can’t abide by it, and that is what we have done with schools.[1]

In the early twentieth century, concern about children’s welfare in oppressive factories was a primary catalyst for enacting child labor laws and simultaneously tightening compulsory schooling laws. Yet, for many of today’s children, the time they spend in forced schooling environments is both cruel and hazardous to their health. Gone are the oppressive factories, but in their place are oppressive schools. Where is the outrage?

In a New York Times Op-Ed article, author Malcolm Harris posits that young people are placed into these high-pressure, increasingly competitive schooling environments by corporate interests aiming to push job training to younger ages without having to pay for it. He writes:

There are some winners, but the real champions are the corporate owners: They get their pick from all the qualified applicants, and the oversupply of human capital keeps labor costs down. Competition between workers means lower wages for them and higher profits for their bosses: The more teenagers who learn to code, the cheaper one is.[2]

Harris’s solution is to encourage students to unite collectively, following a labor union paradigm, to demand better schooling conditions. He asserts:

Unions aren’t just good for wage workers. Students can use collective bargaining, too. The idea of organizing student labor when even auto factory workers are having trouble holding onto their unions may sound outlandish, but young people have been at the forefront of conflicts over police brutality, immigrant rights and sexual violence. In terms of politics, they are as tightly clustered as just about any demographic in America. They are an important social force in this country, one we need right now.[3]

While Harris and I agree that the conditions of forced schooling are untenable and rapidly worsening, we disagree on the solution. To suggest that students unionize to demand better compulsory schooling conditions is similar to suggesting that prisoners unionize to demand better prisons: It’s a fine idea but it’s completely futile. Children are mandated under a legal threat of force to attend compulsory schools.

The first step to addressing the oppressiveness of forced schooling and its harmful effects on children is to fight the compulsion. Rather than trying to improve the conditions of an inherently unjust, state-controlled system, the system itself must be overturned. After all, humans cannot be truly free when they are methodically, and legally, stripped of their freedom under the pretense that it’s good for all.

[1] Gray, Peter. 2010. “ADHD & School: Assessing Normalcy in an Abnormal Environment.” Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/freedom-learn/201007/adhd-school-assessing-normalcy-in-abnormal-environment

[2] Harris, Malcolm. 2017. “Competition Is Ruining Childhood. The Kids Should Fight Back.” The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/06/opinion/students-competition-unions-bargaining.html

[3] Ibid.

Teens Need Less Schooling and More Apprenticeships

Apprenticeships first appeared in the later Middle Ages as an opportunity for young people, usually between the ages of 10 and 15, to gain practical skills and on-the-job training from a master craftsman. These adolescent apprentices came of age immersed in authentic experiences and surrounded by adult mentors.

The term “adolescence” comes from the 15th century Latin word, “adolescere,” meaning “to grow up or to grow into maturity.” But it wasn’t until 1904 that G. Stanley Hall, the first president of the American Psychological Association, coined the term “adolescence” to identify a separate and distinct phase of human development. The expansion of compulsory schooling statutes, particularly for teenagers, as well as new child labor laws, artificially extended childhood and gave rise to the “typical teenager” stereotype that persists today.

Teenagers Are More Capable than We Allow

Adolescence became a social construct. Most of the research into adolescence, often viewed in pathological terms, began in the 1940s. Removed from genuine, real-life experiences and confined to a restrictive, artificial mass schooling environment, it is no wonder that adolescents often respond with apathy, angst, and anger. But this is not how teenagers have historically behaved, nor how they behave today in many parts of the world.

As psychologist Dr. Robert Epstein, author of The Case Against Adolescence, writes:

The social-emotional turmoil experienced by many young people in the United States is entirely a creation of modern culture. We produce such turmoil by infantilizing our young and isolating them from adults. Modern schooling and restrictions on youth labor are remnants of the Industrial Revolution that are no longer appropriate for today’s world; the exploitative factories are long gone, and we have the ability now to provide mass education on an individual basis. Teenagers are inherently capable young adults; to undo the damage we have done, we need to establish competency-based systems that give these young people opportunities and incentives to join the adult world as rapidly as possible.[1]

Apprenticeships can be a valuable, time-tested approach to connect adolescents with the authentic, practical experiences of the adult world. High school-age young people crave real, meaningful experiences that can lead to useful skills and hands-on knowledge. Expanding apprenticeship programs to adolescents can not only address socially-constructed teenage turmoil, but also create a critical pathway for career success and personal fulfillment.

Integration through Apprenticeships

Critics may argue that apprenticeships and vocational education create a “two-tiered” system, in which more advantaged young people take an academic path while less privileged kids get left behind. In the preface of his book, The Means to Grow Up: Reinventing Apprenticeship as a Developmental Support in Adolescence, Dr. Robert Halpern disagrees. He writes that “youth apprenticeship experiences set the foundation for and in some instances actually create more nuanced and grounded post-secondary pathways for many youth, across social class. What might at first glance seem a strategy for reproducing inequality—an academic pathway and extended adolescence for the most advantaged youth, a more vocational pathway and a push into the adult world for the less advantaged—is one means for addressing it.”[2]

Apprenticeship programs are a win-win for both apprentices and the employers who hire and train them. Adolescents gain beneficial abilities and connection to the authentic, adult world, while employers generate a pipeline of skilled workers. Teenagers are not innately troubled. The key is to support their natural development by removing them from restrictive, artificial institutional environments while reintroducing relevant pathways toward adulthood.

[1] Epstein, Robert. 2007. The Case Against Adolescence: Rediscovering the Adult in Every Teen. California: Quill Driver Books/Word Dancer Press, Inc.

[2] Halpern, Robert. 2009. The Means to Grow Up: Reinventing Apprenticeship as a Developmental Support in Adolescence. New York: Routledge.

Education Needs to Be Uber-ized

Uber revolutionized transportation. Airbnb transformed the lodging and short-term rental space. Netflix was pathbreaking in the field of on-demand entertainment. In all of these instances, innovative, agile ideas competed against existing, outdated models. And they won.

I feel bad for the taxi drivers who spent a lot of money for a regulated, now near-worthless medallion, but I honestly can’t remember the last time I called a cab. And the popularity of Uber has led to other competitors entering the space, so if you don’t like Uber and its practices, Lyft and other ride-sharing companies are quickly gaining market share. Disruptive innovations may initially cause some challenges as a market gets re-calibrated, norms get re-shuffled, and workers get re-trained, but more choice and more variety, at different price points and with different levels of service, are generally better for patrons.

The true genius of these three examples of innovations that completely altered their industries is that they did so by simply bypassing the existing, rigid model and going direct-to-consumer—giving end-users a service that was leaps-and-bounds better than the status quo. They also leveraged best available technology to transform their respective fields. I think the same disruptive innovation could work in education, as new, agile learning models gradually grow and replace existing, obsolete conventional schooling. After all, taxis are still available for those who want them, but there are now many other choices.

The Ubers of Education

The possibilities for education without conventional schooling are almost limitless, and we are already seeing many of these models gain popularity and presence. Khan Academy has become a household name for free, high-quality, on-demand, online learning. Khan is joined by other, free online learning platforms, such as Duolingo, Coursera, HarvardX, and MIT OpenCourseWare—to name just a few. YouTube makes learning easy and interesting, whether I am trying to learn how to properly chop celeriac, or my 6-year-old daughter is learning how to preserve and pin the bugs she collects, or my 8-year-old son is learning his latest skateboarding tricks.

In fact, on that last example, a recent Forbes article on the future of learning describes why it was that skateboarders got so good in the mid-1980s. It turns out, that was the first time skateboarding sports videos became widely available—using new VCR technology—and quickly improved skateboarders’ skills. Forbes contributor, John Greathouse, writes:

In the same way action sports videos rapidly accelerated the skill level of millions of participants, augmented and virtual reality will also propel the dissemination of practical, tactile skills across the globe.[1]

The future of learning, interwoven with cutting-edge technology, will also very likely include innovative learning spaces that encourage individuality and invention. Unlike conventional schools, new learning spaces will place less emphasis on order and more on originality, less on conformity and more on creativity.

The Makerspace Model

We already see the seeds of these conventional schooling alternatives in self-directed learning centers around the country. In Boston, Parts & Crafts combines elements of a makerspace and self-directed learning center to create an entirely non-coercive, technology-enabled learning environment for young people choosing to learn without school. The makerspace model is likely to be an enormous catalyst in shaping the new ways in which people, young and old, learn through their community and throughout their lifetime.

Makerspaces and hackerspaces are popping up most rapidly and accessibly in libraries across the country. As an article in the Atlantic explains:

“Makerspaces are part of libraries’ expanded mission to be places where people can not only consume knowledge, but create new knowledge.” And therein lies the startling difference between education of the past and of the future: conventional schooling forces learners to consume knowledge, whereas the future of education empowers learners—of all ages and stages—to create knowledge.[2]

Just as Uber helped to give riders faster, better service at lower costs than traditional taxis, the disruptive education models of the future will be better and cheaper—and much more relevant—than conventional schooling. These new learning models will revolutionize the education field through choice, technology, and empowerment.

The future is here.

[1] Greathouse, John. 2017. “The Future of Learning: Why Skateboarders Suddenly Became Crazy Good in the Mid-80s.” Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/johngreathouse/2017/02/25/the-future-of-learning-why-skateboarders-suddenly-became-crazy-good-in-the-mid-90s/

[2] Fallows, Deborah. 2016. “How Libraries Are Becoming Modern Makerspaces.” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/03/everyone-is-a-maker/473286/

Homeschooling

It's a Great Time to Be a Homeschooler

Homeschoolers are a diverse bunch. Our teaching approaches and learning philosophies vary. Our politics run the gamut and our visions of education reform differ greatly. Yet, despite these contrasts, homeschoolers are remarkably similar. I recently asked a large, eclectic group of homeschooling parents why they chose this education option for their children. Key homeschooling features like “freedom,” and “time,” and “flexibility,” and “individualization” were common drivers for all.

When I first heard about homeschooling, it was 1998. I was a senior in college writing a research paper on education choice and the rising homeschooling movement, and became fascinated by this option. A college classmate of mine connected me with her family members who were homeschooling, and they invited me into their home to observe and ask questions. Of course my first question was: “What about socialization?”

I remember the mom’s calm and eloquent response, pointing out the obvious difference between being social and being socialized. She described their vibrant and engaging homeschooling networks, community involvement, and neighborhood activism. She explained that much of the socialization that happens in schools is not positive and can lead to malevolent behaviors, like cliques, and bullying, and unhealthy competition. Her homeschooled daughter graciously played her violin during my visit, and was one of the most curious, articulate, and polite young children I had ever met. I was hooked.

Later, I went on to graduate school in education policy at Harvard and became more committed to the ideas of education choice and innovation and alternatives to school. Now, as a homeschooling mom to four, never-been-schooled children, I combine policy and practice on a daily basis, watching the extraordinary ways in which my children learn without school.

According to U.S. Department of Education data, the number of homeschooled children doubled between 1999 and 2012 to approximately 1.7 million children, or 3.4 percent of the overall school-age population. (As a comparison, about 4.5 million children are enrolled in U.S. K-12 private schools.) “Concern about the school environment, such as safety, drugs, or negative peer pressure” remains a top driver for homeschooling families, with 34 percent of 2016 Department of Education survey respondents indicating that it was the most important reason in their decision to homeschool.

2017 Homeschooling Report

A 2017 report by The Pioneer Institute, a Boston-based public policy think tank, sheds light on the rapid growth and diversity of the U.S. homeschooling population. Co-authored by William Heuer and William Donovan, the comprehensive white paper explains that despite a paucity of support from government officials—and outright opposition by the nation’s largest teachers’ union—homeschooling has gained in both popularity and reach over the past several decades.

The report highlights that “there is no typical homeschooler or homeschooling family,” as the “one size fits all” prototype of conventional public schools does not apply to homeschooling families who tailor their educational approach to the needs and values of their family and their children. The report states:

Homeschooling is a viable alternative for the many students and their families who wish to opt out of traditional public schools. Regardless of a family’s rationale for homeschooling, the universal tenet of homeschoolers is the importance of parental choice and the conviction that parents are best equipped to make the educational decisions that affect their children.[1]

In tracing the history of 19th century compulsory schooling laws to the modern education choice movement, the report reminds us that Horace Mann, the proclaimed “father of American public education” who passed the nation’s first compulsory schooling statute in Massachusetts in 1852, homeschooled his own three children with no intention of sending them to the common schools he mandated for others.

The report says about Mann:

This hypocrisy of maintaining parental choice for himself while advocating a system of public education for others seems eerily similar to the mindset that is so common today: Many people of means who can choose to live in districts with better schools or opt for private schools resist giving educational choices to those less fortunate.[2]

Demographics and Costs

As the fastest-growing alternative educational option, increasing at a rate of 3 percent per year, homeschooling continues its ascent into the mainstream with families choosing to homeschool for a variety of reasons, from a clear lifestyle choice to a lack of quality alternative education options.

Despite their disparate philosophies on how and why they homeschool, the Pioneer report finds that homeschooling families “have been united in their belief that parental choice in deciding to homeschool and the manner in which their children are educated is an intrinsic right, one which should not be usurped by the state. . . They also hold to the belief that the overall environment of traditional public school systems is not conducive to the educational goals they have for their offspring.”[3]

Legal throughout the United States, homeschooling represents a diverse cross-section of the American population. Demographically, Hispanics now comprise 15 percent of the homeschooling population, and black homeschooling families represent 8 percent—a number the Pioneer report cites as doubling in the 2007-2011 timeframe. Highlighting NCES data, the report reveals that 16 percent of homeschooling parents are educating a child with a physical or mental health issue, and more than 15 percent have a child with “other special needs.”

Homeschooling as an incubator for education innovation

The geographic, demographic, and ideological diversity of the expanding homeschooling population is leading to many pathways of educational and pedagogical innovation. For homeschooling families, education choice starts at home; but as incubators of new methods and approaches to teaching and learning, their choice can have a widespread, positive impact on education innovation nationwide.

A lot has changed for homeschooling and education freedom since the late 90s. While I still get asked that knee-jerk question about socialization that I so naïvely asked years ago, I find it happens less often. Many people know homeschoolers, and some have even considered the approach themselves. Homeschooling networks are diverse, active, and far-reaching, connecting homeschoolers to each other and their community’s resources in myriad ways. Organizations and businesses, museums and libraries, nature centers and community colleges recognize homeschooling’s popular rise and offer classes and resources to meet different needs and interests. Online learning resources allow for easy, on-demand access to a range of topics and subjects. Facilitating learning and pursuing knowledge has never been easier or more accessible. It’s a great time to be a homeschooler!

[1] No Author. 2017. “Study: States Should Provide Parents With More Information About Homeschooling Options.” Pioneer Institute. http://pioneerinstitute.org/featured/study-states-provide-parents-information-homeschooling-options/

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

So, You’re Thinking about Homeschooling. . .

I have been getting emails like the one below more frequently lately, so I thought I would share my general response:

Dear Kerry: I ran across your website while doing research on homeschooling. I am a mother of 3 children ages 6, 4 and 2. We moved to the suburbs when my children were smaller to take advantage of the top-rated public schools in our town. We had a wonderful pre-school experience due to the choice of school focused on play, outdoor exploration and emotional development.

However, as my 6 year old embarks on her education in the public school system, I find myself becoming more and more disappointed. More importantly, I find her becoming bored and disinterested in learning as a 1st grader.

All of this said, I am contacting you because I am thinking of homeschooling and I’m scared to death! What are the resources? What curriculum should I use? Where do I begin? So many questions! Help!

Hello and welcome to the exciting world of learning without schooling! You have already taken the important first step in redefining your child’s education by acknowledging the limitations of mass schooling, recognizing the ways it can dull a child’s curiosity and exuberance, and seeking alternatives to school. Now it’s time to take a deep breath, exhale, and explore.

1. First things first: Connect with your local homeschooling network. This network could be a message board through a Yahoo or MeetUp group, or a Facebook group, or a local or national homeschooling advocacy group. Maybe you have already joined the Alliance for Self-Directed Education and have connected with the local SDE groups that may be forming in your area. Tapping into your local homeschooling community, posting your questions and introducing yourself, can be incredibly valuable. You may be surprised at just how many homeschooling families are nearby and the many activities and resources available to you. You may also find families on a similar path as yours. This can alleviate much of the anxiety you are experiencing as you take a peek into this new world of learning. These local networks can help you to navigate your local homeschooling regulations and guide you through the process of pulling your child from school.

2. Second: start reading! Obviously, you are already doing this or you wouldn’t have found my blog, but there is much more to learn. Homeschooling and education blogs and websites are great resources. Here is my short list of favorite books/articles/films to get you started:

- Free To Learn, by Peter Gray

- Teach Your Own, by John Holt (Anything by John Holt is worth reading. Here is the Holt/Growing Without Schooling website.)

- Life Learning Magazine, by Wendy Priesnitz (editor)

- Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling, by John Taylor Gatto

- Free-Range Learning, by Laura Grace Weldon

- Home Grown, by Ben Hewitt

- The Teenage Liberation Handbook, by Grace Llewellyn

- The Unschooling Handbook, by Mary Griffith

- The Unschooling Unmanual, by Jan Hunt

- Deschooling Society, by Ivan Illich

- Free To Live, by Pam Laricchia

- Class Dismissed documentary

- Schooling the World documentary

3. Third: What about curriculum? Personally, I am an advocate for Self-Directed Education (SDE). Sometimes referred to as “unschooling,” SDE shifts our view of education from schooling (something someone does to someone else, often by force) toward learning (something humans naturally do). With Self-Directed Education, young people are in charge of their own learning and doing, following their own interests and passions, with grown-ups available to help connect them to the vast resources of both real and digital communities. Children direct their education, adults facilitate.

I am a realist, though. (Or at least I try to be!) So I know that it is often challenging for families to go directly from a schooled mindset to an unschooled one. Whenever parents ask me what curriculum they should choose, I say *if* you are going to use a curriculum, I recommend Oak Meadow. A Vermont-based company that incorporates a lot of Waldorf-inspired educational ideas, Oak Meadow is a gentle, rich curriculum with a stellar reputation.

4. Next: think about your family values, needs, and rhythms. Shifting from schooling to learning may involve some big changes to your family life, your routines, and your schedules. It may lead to reassessing priorities and to carefully juggling multiple work and family responsibilities. It also means you need some help to avoid burning out! Consider your support network of family, friends, and community and get the help you need to make this work for the long-term. If there is a self-directed learning center or homeschooling co-op near you, these resources can also be incredibly helpful in enabling you to find balance and connection.

5. Finally: talk with your kids! Learning without schooling is a collaborative endeavor that is mostly focused on your child’s distinct interests, learning styles, and needs. Talk with your child and find out what she wants to do. If you are coming directly out of a school environment, you may need some time to “deschool”—to fully embrace living and learning without being tied to the expectations and accouterments of a schooled lifestyle. Go to the library, the museum, the park, or the beach. Take a walk in the woods. Spend long, slow mornings reading books together on the couch. Bake cookies. Ride bikes. Write a letter to a friend. Watch a movie. Play Scrabble. Go to the grocery store, the bank, the post office. Live life. Soon you will see that living and learning are the same thing.

Best wishes to you as you embark on this exciting life journey! Remember: schooling is a relatively recent societal construct; learning is a natural condition of being human. Happy learning!

Warmly,

Kerry

There’s a Due Process Problem with Homeschool Regulations

At over two million young people, the number of US homeschoolers is nearly comparable to the number of US students enrolled in public charter schools, and it is now considered a worthwhile education option for many families.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, a top motivator for homeschooling parents is “concern about the environment of other schools.” While their homeschooling approaches and educational philosophies vary widely, most homeschooling parents value the freedom, flexibility, and focus on family and community that a homeschooling lifestyle offers. In many ways, this freedom, flexibility, and family-centered learning are terrifying to the state. Despite the fact that homeschooling has been legally recognized in all 50 states since 1993, attempts to limit homeschooling freedoms are ongoing.

Recent efforts to tighten homeschooling regulations have been spotlighted in New Hampshire and Iowa, and homeschoolers in the United Kingdom are now dealing with mounting pressure to make their homeschooling laws more restrictive.

An underlying theme in these calls for regulating homeschoolers is that parents can’t be trusted and government knows best. Considering the fact that US students are lagging far behind their peers in other nations on international comparison tests, and the National Center for Education Statistics reports that only 14% of African-American eighth graders are proficient readers—while homeschooling students continue to outrank their schooled peers in academic performance—we should wonder who really knows best how to educate kids.

Homeschooling opponents will often cite rare examples of abuse or neglect of parents who claimed to be homeschooling, and who were often already known to social services agencies, as a rationale for restricting homeschoolers’ freedoms. The vast majority of homeschooling parents are overly attentive to their children’s education and well-being, which may be a primary reason they chose to homeschool in the first place. Sending their kids to school would be the easy path.

The biggest problem with the often-cavalier way citizens and lawmakers suggest regulating homeschoolers—who receive no public money but still pay local property taxes to fund schools—is that it is an invasion of privacy and a violation of due process. It assumes parents must be monitored for the good of others, and that they are guilty unless proven otherwise. Deep down, these efforts to restrict homeschooling freedoms are driven by fear. There is fear of the unfamiliar and fear for others’ safety and well-being.

Fear of the unfamiliar and fear for others’ safety have previously led us down disturbing paths as a nation. We fear what we don’t know and can’t control. Calls to regulate homeschoolers—often by tying them to a standardized schooled framework with frequent monitoring—originate from fear of who they are and what they do. Eroding the liberties of an entire group out of an unfounded fear of a few bad apples steadily chips away at the fabric of a free society.

“If the homeschoolers are doing everything right, then they won’t mind some oversight,” is a common refrain from regulation advocates. But that is like saying, if I have nothing to hide it’s okay for the government to listen to my phone calls and read my emails. It’s a breach of privacy and an inappropriate use of state power.

We can’t always protect all of our citizens from harm, but we can be aware when trying to protect them may do more harm than good. A free society depends on liberty and choice and freedom from government intervention. Instead of regulating the unfamiliar, we should seek to understand, tolerate, and perhaps learn from what it may teach us.

Homeschoolers: The Enemy of Forced Schooling

I was born in 1977, the year John Holt launched the first-ever newsletter for homeschooling families, Growing Without Schooling. At that time, Holt became the unofficial leader of the nascent homeschooling movement, supporting parents in the process of removing their children from school even before the practice was fully legalized in all states by 1993. Today, his writing remains an inspiration for many of us who homeschool our children.

Holt believed strongly in the self-educative capacity of all people, including young people. As a classroom teacher in private schools in both Colorado and Massachusetts, he witnessed first-hand the ways in which institutional schooling inhibits the natural process of learning.

Holt was especially concerned about the myriad of ways that schooling suppresses a child’s natural learning instincts by forcing the child to learn what the teacher wants him to know. Holt believed that parents and educators should support a child’s natural learning, not control it. He wrote in his 1976 book, Instead of Education:

My concern is not to improve ‘education’ but to do away with it, to end the ugly and anti-human business of people-shaping and to allow and help people to shape themselves.[1]

Self-Determined Learning

Holt observed through his years of teaching, and recorded in his many books, that the deepest, most meaningful, most enduring learning is the kind of learning that is self-determined.

As “the enemy,” we homeschoolers reject the increasing grip of mass schooling.

One of his most influential books, originally published in 1967, is How Children Learn. It was re-published in 2017 in honor of its 50th anniversary, with a new Foreword by progressive educator and author, Deborah Meier. In her early days as an educator, Meier says, she was influenced by Holt’s work and was particularly drawn to his revelation that even supposedly “good schools” failed children through their coercive tactics. Meier writes in the Foreword:

While following Holt’s deep exploration of how children learn I therefore wasn’t surprised to discover Holt had joined ‘the enemy’—homeschoolers. His little magazine, Growing Without Schooling, was the most useful guide a teacher could ever read. As time passed I began to change my views of homeschooling. I’m still first and foremost working to preserve public education but homeschoolers can be our allies in devising what truly powerful schooling could be like. If we saw the child as an insatiable nonstop learner, we would create schools that made it as easy and natural to do so as it was for most of us before we first entered the schoolroom.[2]

Compulsory Education is Always Coercive

The trouble with Meier’s line of reasoning is that it presumes this is something schools can do. Mass schooling is, by its nature, compulsory and coercive. Supporting “an insatiable nonstop learner” within such a vast system of social control is nearly impossible.

Holt said so himself. In his later books, as he moved away from observations of conventional classrooms and toward “the enemy” of homeschoolers, Holt acknowledged that the compulsory nature of schooling prevented the type of natural learning he advocated. He writes in his popular 1981 book, Teach Your Own:

At first I did not question the compulsory nature of schooling. But by 1968 or so I had come to feel strongly that the kinds of changes I wanted to see in schools, above all in the ways teachers related to students, could not happen as long as schools were compulsory.[3]

Holt continues:

From many such experiences I began to see, in the early ’70s, slowly and reluctantly, but ever more surely, that the movement for school reform was mostly a fad and an illusion. Very few people, inside the schools or out, were willing to support or even tolerate giving more freedom, choice, and self-direction to children . . . In short, it was becoming clear to me that the great majority of boring, regimented schools were doing exactly what they had always done and what most people wanted them to do. Teach children about Reality. Teach them that Life Is No Picnic. Teach them to Shut Up and Do What You’re Told.[4]

While progressive educators like Meier may have the best intentions and believe strongly that schools can be less coercive, the reality is quite different. Over the past half-century, mass schooling has become more restrictive and more consuming of a child’s day and year, beginning at ever-earlier ages. High-stakes testing and zero tolerance discipline policies heighten coercion, and taxpayer-funded after-school programming and universal pre-k classes often mean that children spend much of their childhood at school.

As “the enemy,” we homeschoolers reject the increasing grip of mass schooling and acknowledge what Holt came to realize: compulsory schooling cannot nurture non-coercive, self-directed learning. Holt writes in Teach Your Own: “Why do people take or keep their children out of school? Mostly for three reasons: they think that raising their children is their business not the government’s; they enjoy being with their children and watching and helping them learn, and don’t want to give that up to others; they want to keep them from being hurt, mentally, physically, and spiritually.”[5] Today, those same reasons ring true for many homeschoolers.

It’s worth grabbing the anniversary copy of John Holt’s How Children Learn. His observations on the ways children naturally learn, and the ways most schools impede this learning, are timeless and insightful. But it is also worth remembering that Holt’s legacy is tied to the homeschooling movement and to supporting parents in moving away from a coercive model of schooling toward a self-directed model of learning.

After all, Holt reminds us in Teach Your Own: “What is most important and valuable about the home as a base for children’s growth in the world is not that it is a better school than the schools but that it isn’t a school at all.”[6]

[1] Holt, John. 2004. Instead of Education: Ways to Help People do Things Better. First ed. 1976, E.P. Dutton & Co. Colorado: Sentient Publications.

[2] Meier, Deborah. 2017. Foreword to How Children Learn, 50th Anniversary Edition by John Holt. New York: Da Capo Press.

[3] Holt, John. 2003. Teach Your Own: The John Holt Book of Homeschooling. New York: Da Capo Press.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

Homeschoolers: The Enemy of Forced Schooling

I was born in 1977, the year John Holt launched the first-ever newsletter for homeschooling families, Growing Without Schooling. At that time, Holt became the unofficial leader of the nascent homeschooling movement, supporting parents in the process of removing their children from school even before the practice was fully legalized in all states by 1993. Today, his writing remains an inspiration for many of us who homeschool our children.

Holt believed strongly in the self-educative capacity of all people, including young people. As a classroom teacher in private schools in both Colorado and Massachusetts, he witnessed first-hand the ways in which institutional schooling inhibits the natural process of learning.

Holt was especially concerned about the myriad of ways that schooling suppresses a child’s natural learning instincts by forcing the child to learn what the teacher wants him to know. Holt believed that parents and educators should support a child’s natural learning, not control it. He wrote in his 1976 book, Instead of Education:

My concern is not to improve ‘education’ but to do away with it, to end the ugly and anti-human business of people-shaping and to allow and help people to shape themselves.[1]

Self-Determined Learning

Holt observed through his years of teaching, and recorded in his many books, that the deepest, most meaningful, most enduring learning is the kind of learning that is self-determined.

As “the enemy,” we homeschoolers reject the increasing grip of mass schooling.

One of his most influential books, originally published in 1967, is How Children Learn. It was re-published in 2017 in honor of its 50th anniversary, with a new Foreword by progressive educator and author, Deborah Meier. In her early days as an educator, Meier says, she was influenced by Holt’s work and was particularly drawn to his revelation that even supposedly “good schools” failed children through their coercive tactics. Meier writes in the Foreword:

While following Holt’s deep exploration of how children learn I therefore wasn’t surprised to discover Holt had joined ‘the enemy’—homeschoolers. His little magazine, Growing Without Schooling, was the most useful guide a teacher could ever read. As time passed I began to change my views of homeschooling. I’m still first and foremost working to preserve public education but homeschoolers can be our allies in devising what truly powerful schooling could be like. If we saw the child as an insatiable nonstop learner, we would create schools that made it as easy and natural to do so as it was for most of us before we first entered the schoolroom.[2]

Compulsory Education is Always Coercive

The trouble with Meier’s line of reasoning is that it presumes this is something schools can do. Mass schooling is, by its nature, compulsory and coercive. Supporting “an insatiable nonstop learner” within such a vast system of social control is nearly impossible.

Holt said so himself. In his later books, as he moved away from observations of conventional classrooms and toward “the enemy” of homeschoolers, Holt acknowledged that the compulsory nature of schooling prevented the type of natural learning he advocated. He writes in his popular 1981 book, Teach Your Own:

At first I did not question the compulsory nature of schooling. But by 1968 or so I had come to feel strongly that the kinds of changes I wanted to see in schools, above all in the ways teachers related to students, could not happen as long as schools were compulsory.[3]

Holt continues:

From many such experiences I began to see, in the early ’70s, slowly and reluctantly, but ever more surely, that the movement for school reform was mostly a fad and an illusion. Very few people, inside the schools or out, were willing to support or even tolerate giving more freedom, choice, and self-direction to children. . . . In short, it was becoming clear to me that the great majority of boring, regimented schools were doing exactly what they had always done and what most people wanted them to do. Teach children about Reality. Teach them that Life Is No Picnic. Teach them to Shut Up and Do What You’re Told.[4]

While progressive educators like Meier may have the best intentions and believe strongly that schools can be less coercive, the reality is quite different. Over the past half-century, mass schooling has become more restrictive and more consuming of a child’s day and year, beginning at ever-earlier ages. High-stakes testing and zero tolerance discipline policies heighten coercion, and taxpayer-funded after-school programming and universal pre-k classes often mean that children spend much of their childhood at school.

As “the enemy,” we homeschoolers reject the increasing grip of mass schooling and acknowledge what Holt came to realize: compulsory schooling cannot nurture non-coercive, self-directed learning. Holt writes in Teach Your Own: “Why do people take or keep their children out of school? Mostly for three reasons: they think that raising their children is their business not the government’s; they enjoy being with their children and watching and helping them learn, and don’t want to give that up to others; they want to keep them from being hurt, mentally, physically, and spiritually.”[5] Today, those same reasons ring true for many homeschoolers.

It’s worth grabbing the anniversary copy of John Holt’s How Children Learn. His observations on the ways children naturally learn, and the ways most schools impede this learning, are timeless and insightful. But it is also worth remembering that Holt’s legacy is tied to the homeschooling movement and to supporting parents in moving away from a coercive model of schooling toward a self-directed model of learning.

After all, Holt reminds us in Teach Your Own: “What is most important and valuable about the home as a base for children’s growth in the world is not that it is a better school than the schools but that it isn’t a school at all.”[6]

[1] Holt, John. 2004. Instead of Education: Ways to Help People do Things Better. First ed. 1976, E.P. Dutton & Co. Colorado: Sentient Publications.

[2] Meier, Deborah. 2017. Foreword to How Children Learn, 50th Anniversary Edition by John Holt. New York: Da Capo Press.

[3] Holt, John. 2003. Teach Your Own: The John Holt Book of Homeschooling. New York: Da Capo Press.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

Hard-Won Homeschooling Freedoms Are Under Threat and Must Be Defended

Homeschoolers today have it easy. Many of us were in diapers when, in 1977, educator John Holt created Growing Without Schooling, the first newsletter to connect and encourage homeschooling families. Holt and other social reformers provided the support and facilitated the networks that would ultimately lead to homeschooling becoming legally recognized and widespread.

I sometimes wonder about the courage it took those earlier homeschooling parents to remove their children from school before it was fully legal, to chart an alternative education path for their children when they were often the only ones on that road. I sometimes wonder if I would have had the same courage.

Homeschooling Is Going Mainstream

Now, homeschooling is a legitimate education option with the number of homeschoolers hovering around two million nationwide. With expanding numbers come increased diversity as families of all races, classes, religions, ethnicities, ideologies, and academic philosophies tailor homeschooling to their distinct needs and lifestyles. For example, the number of African Americans choosing to homeschool continues to rise, often propelled by concerns of institutional racism in schools, and Muslim Americans are reported to be one of the fastest-growing homeschooling demographics.

As homeschooling has become widely accepted and more reflective of our pluralistic society, it is easy to become complacent. Most of us no longer worry about truancy officers knocking on our doors or wonder where we will need to move next to find a community more accepting of family-centered education. We happily play outside on a spring weekday morning without fear that passersby will worry why our children aren’t in school. We choose from a vast assortment of pedagogical approaches, selecting styles that best suit the needs of our children—not school personnel.

We may forget what a recent privilege all of this is. Our freedom to homeschool as we choose is owed in large part to those courageous parents who came before us. Their choice, and their activism, made our homeschooling choice possible and pleasant.

But the Freedom Is Precarious

Our modern homeschooling freedoms also come with the responsibility to protect those freedoms. While we may not have had to fight to secure our homeschooling rights, we should certainly fight to keep them. As homeschooling moves from the marginal to the mainstream, it can trigger state efforts to curb freedoms, heighten regulations, and increase oversight.

Whether or not we would have had the courage to create these homeschooling freedoms we now enjoy, we must have the courage to keep them.

We are seeing this effort mount in California, as an egregious case of alleged abuse by one family has led to recent legislative efforts to crack-down on homeschooling in the state. Current proposed legislation aims to rein in homeschooling families and require government monitoring, including forming an advisory committee to investigate, and potentially “reform,” homeschooling. As NPR reports: “That could be anything from home inspections to credentialing teachers to setting specific curriculums.”[1]

Now is the time for those of us homeschooling today to show our gratitude to those who came before us by continuing their fight. It is up to us to preserve our homeschooling freedoms from government encroachment so that we may continue to a live a life free of school and school-like thinking.

Whether or not we would have had the courage to create these homeschooling freedoms we now enjoy, we must have the courage to keep them.

[1] Purper, Benjamin. 2018. “California Lawmakers Consider How to Regulate Home Schools After Abuse Discovery.” NPR. https://www.npr.org/2018/04/09/600245558/california-lawmakers-consider-how-to-regulate-homeschools-after-abuse-discovery

Why Homeschooled Children Love Reading

I saw the headline in Monday’s Harvard Gazette: “Life Stories Keep Harvard Bibliophile Fixed to the Page.”[1] My first thought was, “I bet he was homeschooled.”

He was.

The article describes the experience of Harvard University junior, Luke Kelly, who grew up in Mississippi and was homeschooled for most of his childhood. Much of his time was spent reading and he developed a passion for books and literature.

Why did I suspect that a bibliophile college student was homeschooled before even reading the article? Because most homeschoolers love to read—I mean, really love to read. Many of them develop this affinity because they have the time, space, and freedom to read when they want, what they want, how they want.

Released from standard schooling constraints that dictate reading materials and create arbitrary reading levels, homeschoolers learn quickly that books are vital tools for knowledge and discovery. They are not the props of arduous assignments. They are vibrant narratives that entertain and edify.

With homeschooling, reading is not a separate subject to be covered at certain times in certain ways; rather it is an integral and seamless part of overall learning. Trips to the library are not reserved for 40-minute blocks once a week with a librarian-led lesson. Homeschoolers often spend hours at the library, scouting the shelves in search of a good story, seeking librarian advice when needed, exploring the vastness of its real and digital resources.

And boy do they read! My older daughter has read more books in the past six months than I read in my entire K-12 public schooling stint.

Homeschoolers are also able to learn to read at their own pace, on their own timetable, following their own interests. With mass schooling, reading is regimented. Children learn to read in a specific way, following a specific curriculum, at a specific time. Increasingly, that time is being pushed to remarkably young ages. Kindergarteners are now expected to do the serious seat-work previously reserved for older children. Even preschoolers are being pressured.

Erika Christakis, author of The Importance of Being Little, writes about the dramatic changes in early childhood education. She explains that much of this change originates from more standardized, Common Core-based curriculum and high-stakes testing requirements. Christakis writes:

Because so few adults can remember the pertinent details of their own preschool or kindergarten years, it can be hard to appreciate just how much the early-education landscape has been transformed over the past two decades. . . A child who’s supposed to read by the end of kindergarten had better be getting ready in preschool. As a result, expectations that may arguably have been reasonable for 5- and 6-year-olds, such as being able to sit at a desk and complete a task using pencil and paper, are now directed at even younger children, who lack the motor skills and attention span to be successful. Preschool classrooms have become increasingly fraught spaces, with teachers cajoling their charges to finish their ‘work’ before they can go play.[2]